The Inuit Writer and cultural activist was a man capable of great wisdom and generosity to friends – whatever their heritage.

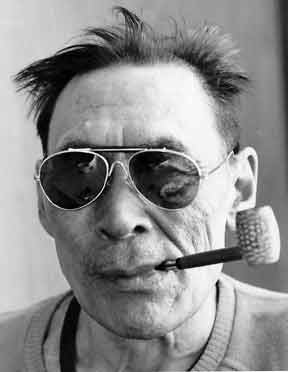

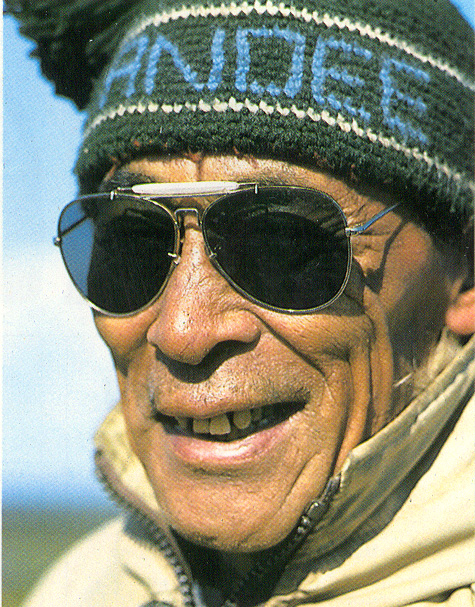

His face was deeply tanned, wrinkled and familiar, like a fine old leather jacket. The eyes, hidden by ever-present sunglasses, were tired, yet not without a sense of possibility. There was a gentle, measured cadence and tone to his voice that implied wisdom without ego, thoughtfulness based on hard-earned experience, and knowledge without prejudice. This was Eric Anoee, a man I had known for all too short a time. Anoee was born in the Kazan River region in about 1924. His mind was always full of wonder, and he understood the power of knowledge early in life. He learned the old ways by watching his father and relatives in the land, and he studied the ways and language of the Qabloonat through the missionaries and their books. This love of learning stayed with him throughout his life. Others regarded him highly because of his increasingly rare understanding of traditional Inuit practices and the richness of Inuktitut.

Anoee became a catechist for the Anglican Church in 1962 and was asked to be an official interpreter for two bishops. In 1965, he started to publish an Anglican magazine. He became a Justice of the Peace and lived in Pangnirtung for several years, where his election to the local council recognized his stature. Soon after the Inuit Cultural Institute in Arviat was formed in 1974, Anoee became a researcher for the Inuit Tradition Project and, in 1975, was appointed its director. He oversaw the recording, transcribing and editing of his people’s cultural heritage and traditions.

The Eric Anoee Readers, written and illustrated by Anoee himself, are used by teachers and classroom assistants to teach Inuktitut throughout the Eastern Arctic. His writing has appeared in Up Here (October / November 1989) among other magazines and in Northern Voices, an anthology edited by Penny Petrone and published by the University of Toronto Press.

When I first met Eric Anoee in 1982, I was embarking on my first full-time teaching job, joining a staff that would be trying to teach over 200 students in a building without interior walls. Eric Anoee would teach Inuktitut to my grade four class. His tranquil, pipe-filled smile immediately warmed me as we shook hands. During that first year of teaching, Anoee was away for several days; I feared he was sick, but didn’t ask anyone. After returning, he politely mentioned “meetings in Ottawa”. It wasn’t until over a month later that I learned he had been south to receive the Order of Canada from the Governor-General for his contributions to education and Inuit culture.

In subsequent years, Anoee would lead Prime Minister Trudeau and the other first ministers into the National Conference Centre in Ottawa to give the opening prayer in Inuktitut for the first conference on Aboriginal issues. During the 1986 Inuit Circumpolar Conference in Kotzebue, Alaska, Eric Anoee was one of the most respected elders invited to address the meetings. On October 16th, 1991, then Northwest Territories’ Education Minister Steven Kakfwi posthumously recognized Anoee with an award for his contributions to literacy in the Northwest Territories. While honours and accolades often came his way, Anoee took his greatest pleasures from his family, his time on the land, his art and his omnipresent pipe. Due to a progressive illness, it became more difficult for Anoee to spend time on the land in his later years. However, it has been said that in his prime, Anoee could build a finished iglu in 45 minutes and completely butcher a bull caribou in less time. Anoee had the respect of his fellow hunters. In subsequent years, Anoee would lead Prime Minister Trudeau and the other First Ministers into the National Conference Centre in Ottawa to give the opening prayer in Inuktitut for the first conference on Aboriginal issues.

Whenever I visited Anoee, I felt overwhelmed by his family’s hospitality. On my first visit, I knocked at the door (a formal habit that I later unlearned), brushed the snow off my sealskin kamiks and edged inside. The porch contained an unfinished wooden shelf unit that looked like a shop project from school, loaded down with the kinds of odds and ends that are essential to Northern settlement life: a litre of 10W 30 oil, two recycled NGK9BR spark plugs, a drive belt for a Yamaha 340 snowmobile, snow knife, a well-used Coleman stove, a can of Naphtha, a greasy toolbox, and a handful of .22 calibre bullets.

The living room was spartan, yet welcoming, with a large grey chesterfield that showed signs of child erosion. Across from the couch was a crucifix and a painting of the Virgin Mary beside it. A broad, lime-green wooden table was surrounded by three chairs that could have come from a 1950s diner. In the corner of the living room was the ubiquitous 30-inch television, tuned to Hockey Night in Canada. Anoee’s wife, Martina, brought us a huge pot of tea made from Wolf Creek ice, guaranteed to yield a better-tasting brew than you could make with trucked-in, chlorinated water. A steaming plate of bannock fresh from the frying pan followed, and a pot of caribou stew (uujuq).

During other visits, I would be ushered to his bedroom, where I often found Anoee reclining upon a single, well-worn mattress, no box-spring, thank you, upon the floor. His CB radio would be squawking out messages from settlements and camps across the North. The aroma that wafted from his old corncob pipe permeated his room. Anoee carefully blended Erinmore flake pipe tobacco with a crop of low bush cranberry leaves, harvested at a precise time each fall. They were roasted and cut so that even in the darkest January, the effect upon the senses was like walking on the autumn tundra.

In this setting, I passed many a warm, memorable evening. Anoee might show me a painting or carving he was working on or ask me probing questions about how to best use his new camera. Another evening, he might tell me a story or teach me a string game. Before knowing him, I had always felt awkward with silence during a conversation; Anoee reminded me that silence gives you time to listen and think. He often sang and laughed readily. This is how I remember Eric Anoee before he died on September 24, 1989, in Arviat. On March 19th, 1991, five days after the birthday of Eric Anoee, my wife Helene and I were blessed with a son. We asked our friend, Elisapee Karetak if she would take a message to Martina Anoee, who did not have a phone. We wanted to ask her if we could name our son after her late husband.

Elisapee phoned to tell us Martina’s enthusiastic answer was “Yes!” The Reverend Armand Tagoona baptized our son in Rankin Inlet. The relationship between Tagoona and Anoee had been a long and close one. As he poured the holy water gently over the baby’s head, Armand smiled and whispered, “Welcome back, my friend.”

To this day, I cannot begin to tell you how good it feels to look at my son and say, “I love you, Anoee!”