Category: Family

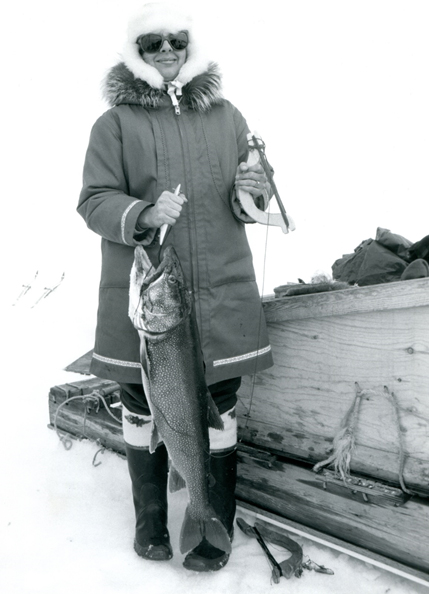

Helene’s Fish

Ellie

Cyberparenting 101

Impressions From My Youth by Lucille Langevin

Impressions from My Youth (audio narration)

By Lucille Langevin

(For Hélène)

Prologue

I was born in 1923, and I was 37 years old when my last child was born. She was in the last of the post-war baby boom, for there was a 15-year gap between her and my firstborn. She came into a world of Rock and Roll, fast cars, instant cake mixes etc. By the time she was six or seven, the eldest of my six children were already on their own. I very seldom talked about the past, having been told often enough that the “Good old days” were for the old; that we were the squares; that we had been brained-washed. However, whenever a mention of events that had happened in my childhood was referred to, my youngest, Hélène, would inquire. She wanted to know more about this strange world I had lived in; her inquisitive little mind was curious about the past. So, to my dear little Hélène who is now teaching Inuit children in the Northwest Territories, I dedicate to you these fragments of the days gone by.

My Father and Brother

When my father was a little boy, around 1890, there was a notice put up in the post offices in the rural Québec area where he lived. The notice said that the Government would pay two cents for every live frog delivered to the station master. There was a great scarcity of frogs in the Maritime provinces, and the insects plagued the farms of that region, so the plentiful frogs of Québec were needed badly. What a great pleasure for a boy of ten to catch frogs and to be paid for it! The pond behind the house and the sides of the river that ran through the south boundaries of the farm was raided for the creatures. With the help of his father, 700 frogs were delivered to the station master in very short time.

My father’s first communion was coming up, so the money from selling frogs was used to buy a lovely piece of blue serge material. His mother had died when he was three, so his older sister Marie cut up the material and sewed him a beautiful suit, which was the very pride of not only of himself but the whole household. In those days, a little farmer boy wore such a fine garment only to go to church on Sundays and religious Feast days. It was taken off as soon as he got home, on Mondays, it was brushed and pressed as well as the other best clothes for Sundays and hung back in the clothes press; as a result, the best suit never was worn out, it was just outgrown in no time at all. So, it was with my father’s precious attire; it was pressed, wrapped in tissue papers and put in a trunk in the attic. My father was the only boy after seven older sisters.

The years passed. My father got married and had children of his own. When my older brother was eight years old, an epidemic of Scarlet fever raced through our quiet village. My brother brought that fearful disease from school to our house. My younger sister and I were quickly dispatched to one of our aunt’s homes while the house was quarantined. There was nothing to fight the fever that raged in my brother’s body. After a month of great suffering, the tumour that had formed into his head broke, and he died. The doctor said it was Meningitis. My father and mother were heart-broken, he was their oldest and held all their hopes for the future, he was such a bright lad.

During his illness, he had grown a lot, and when they came to lay him out, none of his clothes fitted his emaciated body. My father went to the attic, and he brought down a beautifully made blue serge suit. It fit my brother like it had been made for him, this is how I remember him, in a long, white casket in a beautiful blue serge suit, his hair shining like an angel’s.

Grandfather’s Jackknife

Children have very sensitive little souls, and they do not blurt out everything as we tend to believe. My grandfather lived with us. Every morning, my brother Albert and I always tagged behind him as soon as I was able to walk. We were taken for a morning stroll in the “coteau”, a hilly, wooded, crest of land, that zigzagged by a rough road that went to the cultivated fields beyond. There were all sorts of trees. The smell of the pines enveloped us, there were pine cones to play with, and berries to pick in season. There was also a marsh where irises grew in its muddy flanks. Big black crows mocked our childish singsongs. Our grandfather went slowly and sat on tree stump smoking a pipe, resting himself for a while, in the meantime, we picked daisies or dandelions. We watched squirrels scamper up the trees, and chased butterflies.

Grandfather had a very useful jackknife. While he rested himself on the stump, he cut some sort of branch off a willow tree. He worked at it with his knife and tapped the bark off. Pretty soon my brother and I both had new whistles. We resumed our walk. I imagine the noise of our whistles annoyed him after a short time because out came the jackknife again. He used it to pick off resin from the pine trees and gave us both a chunk of it to chew; it was his kind of gum. It tasted nothing like the bubble gum our grandchildren are chewing now. I hated this pine gum, but grandfather said, “It was good for you.” He said that it would give us an “appetite” as if we ever needed gum to do that! Nevertheless, we did not want to hurt his feelings, so we chewed the stuff.

After another short run, the old man would sit again on a rock. Then, out came the magic blade again and he would proceed to scour his pipe with it. I can still hear the scraping sound it made going around the pipe bowl. By midmorning, we were back at the house. We went immediately to the fruit orchard and saw what was ready to eat. If it were apples, grandfather would pick up a couple of the most delightful apples; then we would go to the back of the house and sit beside him on a log. We listened to his stories, and he told us of his youth while he peeled the apples with the ever-present blade of his jackknife. He would slowly quarter the apple and offer us the quarters speared on the magic blade. Grandfather would say, “It’s good children, isn’t it?” We would say, “Yes grandpa”, but it tasted like tobacco juice. I hated it, but we did not want to hurt his feelings, so we ate the quartered second apple just the same, even though it was flavoured with old tobacco juice.

Visiting My Godmother

One of the happiest memories of my childhood was when we would visit my aunt Blanche, who was also my Godmother. I spent a week there during the Christmas season. She was one of my father’s sisters and lived in the country on a bluff overlooking the St-Lawrence River. The first Sunday following Christmas, after the High Mass, my aunt and her husband Amédée, would come for a visit to our home. I would wait anxiously to hear her say, “Well, la petite, are you ready? “

I would look at my mother, and she would say, “Aren’t you going to be lonesome? Do you want to go?” My head would vigorously nod, yes!

It was about three or four miles riding in the cutter under the fur robe, on a wind-swept winter road along the St-Lawrence River. The wind must have come directly from the Arctic, for it was that cold. In the winter the roads were grated by a horse pulling a wooden scraper held by a man, much in the same manner that the fields were ploughed. The road was marked at intervals by the top of little fur trees stuck at each side in the snow banks. There were always bells attached to the horse’s harness; they rang merrily. In a blizzard, they served as a security measure, for the road was a single track, and should anyone meet, the man who prided himself on having the better horse would take to the snow bank. The horse plodded in the snow up to its belly. Many a cutter was up-ended in the snowbank at times like these, it was also a way of showing courtesy to an older driver, or a lady driver, every one saluting each other, but I am deviating. Let’s return to our ride beside the St-Lawrence River, which is a treat on a beautiful winter day, for you can see the majestic Laurentian Mountains rise beyond in all their blue and white splendour.

We had to turn off the main road to go to my uncle Amédée’s place and to go up to the ridge. The hill was so steep; my uncle had to get out of the sleigh and walk beside it. I was sure the horse would not make it to the top, but it always did. After a sharp turn to the right, there was the barn, and a little further up the ridge was the squat grey and greenhouse of my relatives perched on the side of that bluff like a bird in a nest. On the other side of that narrow road, the land was still on a very steep incline. The snowdrifts obliterated everything else, all one could see was a wall of white.

The household consisted of my uncle’s mother, a little, old white-haired lady, always dressed all in black with a white apron tied at the waist, there was also aunt Emely, another sister of my father, she was a spinster. There were two completely white-haired cats with blue eyes; they were both very deaf. There was Bilou, a black and white long-haired dog with the tail curled like a zero; it had a very sharp bark and teeth, it resented the affection my aunt gave me, and to this day, I don’t like little long-haired dogs with sharp barks.

It was a very cold house for those used to central heating; it had only one wood stove, with its pipe going through my grandmother’s room. Aunt Emilie’s room was freezing; I slept there in her bed. It had hand-woven wool sheets on a feather bed into which I buried myself, wrapped in my long sleeves and a high-neck flannel nightgown. On top of us, there were handmade quilts of many kinds. To make sure I would not be cold; aunt Emilie would spread out her racoon coat. I slept very well. In the morning the ice would cover the wash basin. The water in the pitcher had frozen, you could see your breath in the air. Speed dressing was the order of the day. The smell of bacon was already in the air. Blanche would have an orange already peeled for me. She really loved me; she had married only at 40 because she had wanted her school teacher’s pension and consequently taught school for 20 years in the rural area. Uncle Amédée, who was the butter-maker of the parish, had patiently waited all those years for her. They never had any children. When I went to their house, they spoiled me, giving me candies and oranges, treating me like a little princess. One of the things that fascinated me was the way they kept the wood cuttings for the stove. When one wanted to put a slab of wood in the stove, one knelt down in front of the stove and opened a little trap in the floor. Attached to the floor was a rack full of burning wood slabs. The pieces of wood were shoved into the stove, and then the trap in the floor was shut. Uncle Amédée went to the basement every night to replenish the wood box; the wood would be piled almost to the ceiling.

I would dress warmly and then go sliding on the bluff. I had to go around to the back of that mountain of snow, climb to the top, sit myself down, close my eyes, and let myself slide on that steep incline. Half an hour latter l would come in like a miniature snowman with red cheeks. My aunt Blanche and Emilie would fuss over me and peel me another orange. At night my uncle would rock me by the fire. I was a princess for a whole week!

Grandmother

Our maternal grandparents lived with us; it was a big house and half of the house downstairs was their quarters.

Grandmother was an amazing woman. She had the skills of a seamstress, shoemaker, handyman, banker, and grand vizier of my childhood imagination. There was nothing that she couldn’t do. She made my first school bag, a shiny black bag made of what we called “cuir ciré”, which is oilcloth or vinyl. She also made my school uniform as well as everything that went underneath it. She made a quilt with infinite precision, for she was a perfectionist in all her doings. I remember that my doll had cracked her head, they were china-head dolls in those days, with eyes that opened and closed, and they cried when turned on their stomach. So, I knocked on grandmother’s door. The problem was being addressed in my grandmother’s lap. We called her “Mémère” which is an affectionate term in old French. So Mémère said she would put my doll in the hospital to make her get well. It was a few weeks before Christmas that this accident happened. She told me that she would not get out of the hospital until Christmas arrived.

Father always cut our tree from our woodlot. It was a beautiful tree, with almost perfect symmetry; it had the biggest, shiniest balls ever. All sorts of small candles were clipped to its branches along with fine birds and angels with wings of silk, but the miracle was there under the tree: my doll, “Yvonne”, had come back, she even had hair on her head when she had not even had any before. She was wearing a new pink organdy dress all trimmed with laces and wonder of wonders, the dress had pockets, and they were full of jelly beans for me. The magician was also there, smiling at the intense joy given to her granddaughter.

Our grandfather Alfred was afflicted by Parkinson’s disease. We were terrified of him. There was often nobody there to help him. When he started to walk, or shuffle, he would zigzag until he met a wall. We were scurrying away like mad, to us he was a boogie man, and we disappeared really fast. Mémère took good care of him until he died. He was paralysed for almost 20 years.

She had a cupboard in which she kept the tools of her many trades; there were pots of glue, nails, hammers, thumbtacks and special tools to remove them, balls of string, paper bags, assorted boxes full of mysteries. Mother always went to Mémère when we were short of money for an emergency. Mémère made us paper dolls out of newspapers, they all held each other by the hand. She made them of all sizes for our greedy fingers, when the baby came crawling in, she would swing him on her foot holding him by the two hands and make her foot go up and down to the rhythms of old songs,” Ah, Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser” – “Sur le Pont d’Avignon”. She was a very frugal woman. I remember her eating curdled milk with maple sugar, today we call it yogurt. I don’t like it, but I eat it because the girls at the office tell me it’s good for me, but every time I eat it, I think I think of my dear old Mémére. She helped her fellow man all her life. When she was in her 80’s M. le Curé said to her, “Listen I’m a good lad, you paid for your funeral when you were in your early 70’s, but now the prices have gone up, you should give me more money”. She answered him, “Well, it’s not my fault if the good Lord has forgotten me down here, I cannot go yet, so use the interest from the money I gave you.” She lived until 98, she loved us all and never troubled anyone. I wish she was still here; I would tell her she was a unique woman and that I still love her to this day.

The Blacksmith

When one lives on a farm, rainy days are used to attend to the shoeing of the horses, repairs of farm equipment like harnesses. The womenfolk would attend to their mending, do baking and more.

In my preschool days, I was often sent either to the shoemaker or the blacksmith to remind my father of some errands my mother wanted to be done or to tell him dinner was ready; when he went to either place, he met with his contemporaries and lost all notion of time. They exchanged yarns, bragged about their respective horses and learned of the latest happenings or scandals in the four corners of the parish. In those rural parishes, the population at that time was about 3,000 people, and everyone knew everybody else. Half of the parish was related to the other, the hates, loves and foibles of everyone were no secret.

When I recall my short visits to other places, the smell is what first comes to my mind. The shoemaker was a lean, little man with a hump on his back. The endless rows of shoes to be repaired were amazing, to my child‘s eyes, lots of them were beyond repair. Harnesses were hung everywhere. The amazing sewing machine was right behind the counter. The smell of shoe polish and leather permeated everything, even when I was out in the fresh air, I still smelled of shoe polish. When I graduated from my first school bag, my father took a skin of calf leather to him, and that little shoemaker with the dirty hands made me a beautiful large school bag that lasted well all through my primary school years. It must still be in the attic at my brother’s place.

When I went to the blacksmith, it was a visit to a sort of hell. We had an illustrated catechism book at home and one page depicted “Hell”. There was a grinning demon with horns sprouting from his head, a long tail dragging behind him. He was sitting on a throne of fire while other demons dragged the victims of the seven capital (mortal) sins in front of him, there were fires everywhere, snakes and monsters breathing fire, etc. As soon as I stepped into the smith’s shop, the acrid smell, the big red fire, the noise of chains and metal clanking, that page of catechism sprang to my mind. I looked for the devil, and there he was! My terrified little body shook at the very sight of him. He was completely bald under the black cap that he wore. Everything about him was black, his skin, his hands, his leather apron, his shirt, his trousers, except his teeth, they were very white. Horror of horrors, he had two big gold teeth, one in the front and one in the side. When he saw me, he favoured me with that awful golden grin. I cringed right away behind my father who was usually sitting by the big wide door on a keg of nails, smoking his pipe quietly with other old cronies.

That blacksmith would take a red horseshoe out of the fire with tongs, put it on the anvil and hammer at it a few times. Sparks were flying all over. He would go to the horse, and with his back to the rear of the animal, he would take the horse’s back leg between his knees and fit the horseshoe to the hoof. The smoke would come off the hoof with a hissing sound, and the blacksmith would take nails in his leather apron’s pouch and pound the nails into the horseshoe to the hoof of the horse. Wham! Wham! Wham! I could not understand why those big horses would not kick that round little devil of a blacksmith right then and there. He enjoyed his work, and those big beasts were just as placid as could be. The name of the blacksmith was M. St-Pierre.

The Peddler

“Eugénie Gros Oeil” was the name of the peddler who regularly came to our house. She was a tall, manly woman, dressed like all women of her age at that period: all in black, including her hat which was in the shape of a stovepipe of about 8 or 10″. My grandmother wore one of about the same style, except it had a drapery about it. Mlle Eugénie was named “Gros Oeil” because she had a glass eye which was like a clouded blueish stone that rolled at an odd angle from her good one. She earned her living by going door-to-door on foot to her regular clients, which brought her to our house three or four times a year. She carried two portemanteaux (cardboard suitcases). They contained lengths of tissues, mostly printed gingham, needles, thread, measuring tapes, ribbons, laces, and a few accessories like babies’ socks, etc. When mother or grandmother asked the price of a certain item, she held that piece under her good eye and passed it back and forth while stroking it and the verdict was either 10 cents a yard or 15 cents a yard for calico and twenty-five for more expensive fabrics. I don’t think she had anything worth over seventy cents in that valise. My grandmother usually bought something like elastic and thread. My mother encouraged her as well.

She closed her porte-manteaux and was on her way in that waddling gait of hers. We, children, were always in awe! Also, we were afraid that if she looked our way she would cast a bad spell on us and something terrible would happen, she looked so much like a bad old witch! We were told never to laugh at her, or else! So, we always dreaded and delighted in her regular visits.

Le Père Noël

There were moments of great joy while we grew up and the visit of the Père Noël was one of them. On the last Sunday before Christmas, Santa came to town. He was sponsored by the “Compagnie Paquet” of Québec city in cooperation with the local merchants. After the High Mass on that particular Sunday, all the rural school children went to the Town Hall, while the boys of the college of the “Brothers Maristes” and the girls of the convent of the Sisters of Charity went to their respective institutions. A notice was given up by the priest in the pulpit after the sermon, and that was the best announcement that the priest made in the whole year.

Santa went first to the Town Hall, then to the college, and finally, he arrived at our convent. All the time we waited for him in the recreation room. This special room had a partition wall at one end which opened up onto a stage which was, in reality, the music room where all the pianos stood, and music lessons were given. The other end of that room also had a partition wall. On the other side was a regular classroom, for an occasion such as this, that partition was opened-up. The pupil’s desks and benches were all pushed to the far end, and we created one large hall; the pianos were also pushed way back of the stage platform giving ample room for actors or performers which in this case, was Santa himself.

Under the direction of the music teacher and her favourite piano, we sang Christmas carols until that beautiful apparition showed up.

What a glorious Père Noël!

He was a tall man with an unusual round belly, and he was dressed magnificently! His coat and britches were of bright red velvet, trimmed with beautiful white fur, the trim around his hat, the collar on his jacket as well as the closing of it down the front and the wide cuffs all that was of beautiful white fur, he had beautiful long white hair and his beard as curly as was his hair, cascading down all the way to his big wide leather belt, this belt had a large silver buckle. His laced boots came up to his knees, and they were also of fur, it looked like the kind of reindeer with the fur still on it, he had mitts with very large cuffs also of reindeer skin, and he came in accompanied by Mother Superior who escorted him to the stage. He carried this huge sac slung over his shoulders and yelling “HO-HO-HO! Bonjour mes enfants! HO-HO-HO! all the way to the stage; a three-step stool in front of it gave it access. We went wild. Our eyes were round. Our hearts beat faster. We clapped our hands in a mad frenzy. He made a gesture for us to stop yelling and we calmed down instantly. He asked us if we had been good all year and said that Mother Superior had given him a good report and he was going to sing us a song. Immediately the Sister, who was the Director of Music went to the piano and started playing, and Père Noël’s rich voice filled the hall, this is what he sang:

Petits enfants, vous avez une mere

Qui chaque soir veille votre berceau

Pour elle au ciel offrez une priére

Aimez la bien au déla du tombeau.

Dernier amour de ma vieillesse

Venez a moi petits enfants

Je veux de vous une caresse

Pour oublier

Pour oublier mes cheveux blancs.

That is all I remember of that song. I can still sing it to this day, and it does my heart good. His voice was rich and loud, and he sang with gusto! We all had goose pimples.

Then the sister pushed forward an armchair. Père Noël sat down, and we proceeded in single file, in front of him, and with the sister helping him we each received a little brown paper bag with a handful of mixed candies in it. He then departed amidst cheers and yells of joy and happiness. It was usually a very cold and snowy day down there alongside the St-Lawrence River, but we loved it!

The “Good Old Days”

The “Good old days”, as they are referred to were not really good days, people worked just as hard as they do today, but it was not under pressure. The priorities were to have enough food stored away for the long winters, enough warm clothing to encounter it and to stay healthy. Very few families were exempt from sickness. There was an epidemic of Scarlet fever, chicken pox, measles and whooping cough, which ravaged the country and left little white coffins everywhere, these diseases were feared by all mothers. Polio was a killer and dreaded most of all. Hygiene was not at its best, and a lot of old people really stank. Men chewed tobacco and spat; every household had spittoons, even the church had some. Depending on how wealthy the family was that owned the pew, their spittoon was either in porcelain, aluminium, or a plain wooden box with sawdust in it,

Each family had its own pew. The first of January was the time of the auction for the pews. If the previous owner had died, or a family wanted a larger pew or a better-situated pew or a family had neglected to pay the dues for their pew, that pew went to auction. There was quite a competition for the best places. At that time, our parish counted some 3000 souls, and at the High Mass on Sunday all the pews were occupied.

Now when I go back home, the church is spic and span, the old wooden floors have been replaced by shiny tiles, even the epitaph on the walls of the church marking the places of burial of our ancestors beneath the church have all been removed. Nobody owns a pew anymore. Now it is first-come, first-choice of places, but very few places are occupied today. I close my eyes, and I see the ghosts of all the people I knew, all the relatives, grandparents, mother, father, friends. I remember which pew was occupied by whom, all those parishioners have gone. My generation will be the next to be sleeping on the hill. It’s not a bad place really, as a matter of fact, it has the best location. Our cemetery was about one mile from the church, on top of the hill, from where one can see the St-Lawrence River and those old Laurentian Mountains behind it in all their glory. One sees the village and the church in its midst, only the bells ringing in its spire disturb the peace. The air is clean. I would not mind having my bones whitening there at all.

While I am on the subject of the dead, funeral parlours did not exist then. My mother was the first one in our family to go to such an establishment.

The dead were waked at home in the parlour, and it was sometimes a three-night wake because relatives who lived far away were waited for, so they could have one last look at their loved one before the burial. It was a lugubrious wait.

When one passed away, the family sent for the “Croque-mort” who is the man who prepared the dead for the coffin, along with the dead, the family sent the clothes that the deceased was to wear. The next day, the Undertaker came back with his cargo and set up the funeral parlour. The blinds were drawn and were covered with black hangings. The background of the banners was black, and they were depicting angels carrying the cross or other saints, these pictures were in colour. The coffin was placed on a threshold draped with a black covering. On the wall behind the coffin, there was a banner depicting the Sacred Heart of Jesus or the Blessed Virgin or some other Saints. Candelabras flanked each end of the coffin along with ferns on stands. Everyone that came brought sympathy cards all edged in black and put them in the coffin or on little tables placed for that purpose. there was Holy water with a sprinkler also at the disposal of those who wished to use it. At the outside door was placed a black crepe, usually ornamented by a wreath, tied with a purple ribbon.

People came in, knelt down on the kneeling bench placed in front of the coffin, usually covered in purple or black velvet and said prayers while looking at the deceased. If they were close friends, they cried, then they offered their sympathies to the members of the family present in the parlour. The priest came in every night and said the rosary with the family and everyone present. Everyone talked in a whisper and all night, every hour; the family gathered to say the rosary. Sandwiches, coffee, cakes were served at all times.

When a member of a family died far away from home, the body was sent to his father’s house in his hometown and was waked there and buried in the family plot. My brother still owns the ancestral family house, and if the ghosts of all the people who were waked within its walls were to show up, there would not be room to house them all. My husband says that our home lS haunted, but I sleep very peacefully in any room because all the ghosts know who I am and I knew quite a few of them.

In French, a “pleureuse” means one who cries. It also applied to the veil attached to the hats of widows. When a woman lost her husband, she went into mourning for a full year meaning wearing only back outer garments from her head to her shoes and also a semi-transparent veil over half of her face for the first six months after this period, she could remove the veil from her face but kept the “pleureuse” which was a sort of drapery of black crepe on the side of her black hat falling down to her shoulder. After the first year was up, she wore a “semi-deuil” (half-mourning): which was black and white colours only. She could wear black and white prints, white hats etc. for six months after this, pale colours only, nothing ostentatious, for the rest of the year. After this, it was over; she could resume any attire she wished. Not all the widows observed this rule for the full time, but my grandmother surely did. Men wore black bands of ribbon on one sleeve at the upper arm and also on their hat, black shoes, ties for a long time.

The letters one wrote or received from one in mourning were etched in black all around the stationary with 1/4″ of black, the same with envelopes. Mail addressed to a widow always mentioned that fact: Mrs. widowed Jane Doe.

One could tell by the church bells ringing if a man or woman died. For a woman, one bell tolled twice, stopped, and tolled twice again, then stopped, then the three bells would ring in unison. If the one bell tolled three times, it was a man. Everyone wondered who had died if someone knew of a person gravely sick they would say, “Poor Mr. so and so has died”. It did not take very long before the whole parish knew who it was. Men uncovered their hair, and the women bowed their heads, some knelt down when they met the carriage that was carrying the priest with the last rites for someone sick; the driver was ringing a handbell all the way to warn people to clear the way for the priest was carrying the consecrated host.

The hearse was a magnificent piece of equipment. Depending on the affluence of the deceased, it could be pulled by two, four, or six horses all draped with black nets with a black pompom on their heads. The black ornamented coach had a seat up high in the front where the undertaker and his helper sat in all their finery. Their ceremonial attire was the black tails, striped trousers, top hats, gloves, gaiters; it was very formal. The black coach had side windows all dressed with purple-fringed curtains, and one could make out the coffin at the parting of the windows, standing on a chromed rack for support.

It was a very cold morning on the 31st of January, 1950 when my father died. The hearse was pulled by his very own two black horses, the white foot of one having been blackened with black shoe polish; they had on the black nets and the pompoms on their head. The same bells had rung for his wedding on the same day in 1921.

As I sit in my high-rise apartment watching the traffic below, I realize that my generation knows two kinds of world and they are so completely different than the changes accomplished in the last fifty years have made my first world obsolete. when I was a child, we ran outside at the sound of a two-seater airplane. I remember a little plane landing in the field behind the convent and the pilot was charging five dollars for a few minutes ride up. The daughters of the doctor went, but I was too young to go and besides, my parents did not have that kind of money to squander. When the 5-100 German blimp came over, it followed the St-Lawrence River, and the radio announced the times it would pass at Riviere du Loup, Montmagny, Quebec etc. We waited and watched for it, what a wonder!

City Kids, Country Kids

We had an uncle who lived in Montreal and in the summer, he sent his two youngest daughters and his son to our place, so they could have some fresh air. They lived in the St. Henry district of Montreal (made famous by Gabrielle Roy in her well-known book, “Tin Flute”. My uncle’s name was Symphorien. He had a fruits and vegetable business. He bought truckloads of produce at the Bonsecour market and supplied the local grocers.

My cousins did not like to come to the country and live with their bumpkin relatives. At first, they could not sleep at night because it was too quiet. They did not hear the sounds of the streetcars. It was too dark for them. We did not have a street light in our little village. After a while, they got used to our kind of food and our kid of darkness, but they were terrified of bats. There were plenty of those creatures near us because of the trees surrounding our house. On rare occasions, a bat would enter through the shutters in the window. Of course, we did nothing to alleviate their fear. We told them that the bats would cling to their hair and suck their eyes out. They were terrified of everything like children from another planet!

They felt superior because they ate chien chaud (hot dogs) we had no idea what a hot dog was. They told us about all the soft drinks and chocolate bars they were eating in town along with other food we did not know, but they certainly loved the big cakes, strawberries with whipped cream, roasted chickens, large boiled dinners with all the fresh vegetables from our garden. After a few weeks of playing tag and running around with us in the orchard and over the fields, they even began to look like us; they had lost their city whiteness. They thought our barn smelled awful, but they enjoyed jumping with us in the fresh hay. Our aunt sat on the veranda and embroidered endless tablecloths.

Years later, at the age of nineteen, I came to Montreal. I couldn’t get over how bad it smelled in the city, especially where my uncle lived. It was very dirty the houses were full of soot. The windows full of coal dust and a hot dog did not have great appeal to me.

I did get acquainted with Chinese food and also Italian spaghetti, both left me unappreciative. I was told they were tastes to be cultivated, which I did later in life.

After residing in Montreal for a very short while, I realized that my relatives were not living in a favourable part of this beautiful city and soon found myself a brighter corner to live in.

Harvesting

I must have been a very active little girl. In the spring, grandfather would turn over the sod in the garden and under the rich black earth, big fat worms were sticking their heads out. I would pull them and put them in a can with some earth for grandpa to go fishing, but a few found their way in my little apron pockets, and when my older brother came around, I would grab a fat one and run after him to try to put it in his neck, he would run screaming to my mother. To me every season was fun. In the fall, all kinds of apples and plums were there for us to eat. The garden was rich in colours, full of ripe tomatoes, cauliflowers, cabbages, melons, pumpkins, carrots and more. The potato harvest was another fun day; everyone pitched in. The furrows were opened with the plough, and all the potatoes were cascading down from the open earth. We had baskets to put them in. We emptied the baskets at different spots in the field to dry. Soon we had huge mounds of potatoes here and there. Then they were sorted, the big ones and the little ones were to go to feed the pigs. There was a big round iron pot that sat on top of an old-fashioned stove in the pig house. They were cooked in that pot and were mashed with a huge wooden masher made somewhat like a baseball bat Some meal and other grains were mixed into that, how the pigs loved it! The nicer potatoes were stored in their allotted bins in the cellar of the house.

In the spring, the seeds were cut up from that reserve. I always enjoyed the harvest of potatoes, running from one end of the field to the other while grownups were complaining of sore backs, happy that the day was over. Harvesting the wheat was another fun day. It lasted quite a few days; for weeks the harvesting machine had been going, it was a very fine machine. It cut up the wheat which climbed, all lined up sideways, on a sort of conveyor. Once every few minutes a big bundle of wheat, already tied up with string in the middle, was thrown out. These bundles were stood up in groups of six, three facing three others and left on the field for a day or more to dry, then they were picked up and brought up in the barn to wait for the trashing day. Many people helped on thrashing day. The machine was made to work with a long conveyor strap that went around the wheel of a steam engine. It made lots of noise. My father would stand on a little platform at the mouth of the thrashing machine, and he would feed the machine the wheat while wearing long gloves. One man would be pitching a bundle down from the heap; another man would grab that bundle quickly put it on the tray table at the left hand of my father who was cutting the string around the bundle at the same time. My father kept spreading the wheat and feeding that monster machine. At the side of that machine were two outlets where the grain was running down into buckets. another man was tending those buckets, as soon as one was full, he would switch it to an empty one and then empty the full one into a burlap sack, it kept him very busy. At the other end of the machine came the straw and much dust, it needed two more men there to clear the straw and pitch it into a barn compartment for storage; this served as fodder for the animals in winter. For my part, I was a supervisor of everything, munching on apples all the time, when I was old enough to help. I knew everything that had to be done without being told, but could not do very much because the dust made me have terrible nosebleeds, and I had to stay away from it. Thrashing took three or four days. The sacks of grain were stored on the second story of the hangar and on rainy days, when there was no work that could be done outside, my father would pass the grain into the manually operated separator; this machine sorted the good grain from the bad. The good heavy grain had an outlet, and the shaft or light grain also had one. The grains were put in different bins according to their category. Some grains were taken to the mill to be ground into meal for the animals; other grains were fed to the horses and chickens; the best was stored for seeds.

There was a day to harvest turnips; we grew a field of it. The leaves were fed to the cows and other animals; there was a manually-operated machine that sliced turnips. Each cow had a box in front of her stall where they had a feed of turnip along with their hay in the winter; each one also had a drinking bowl that automatically refilled itself when emptied; come to think of it that barn was not a bad barn!

Mademoiselle Elyse

Mademoiselle Elyse was a dressmaker. One day, my mother decided that my sister and I needed new spring coats. Grandmother was away visiting at one of my uncles and was not due back for another month. I must tell you that my mother was a very robust person. When she was married, she weighed 168 pounds. She told us later “It didn’t show my size because I was very well-corseted”. I remember my mother was always stout, even though she was well-corseted, she weighed 220-230 pounds. When she died at age 77 years old, she still was 210 pounds and had never been in a hospital of her life. One day she decided that her wedding suit would make my sister and I some very smart spring coats. It was of a very fine wool cloth of a plum colour. The suit had been ripped out at the seams carefully pressed, and we went to Miss Elyse. Mlle Elyse was a fine looking old maid. My sister was four, and I was six. My mother explained the object of our visit. We were in Mlle Elyse’s kitchen, a big room that was also the sewing studio. In the corner was one of those wire dummies with a partially finished garment on it. Beside a window was the sewing machine and beside it was a cutting table. On a wall were hooked nails, all sorts of cardboard patterns, pin cushions tapes, and scissors. An ironing table stood in another corner; the iron was on the back of the stove. Electric irons had not reached into our part of the world yet.

Mlle Elyse asked my mother if she had any style in mind for our coats. So, my mother said, “Ah yes, do you have the Eaton catalogue?” So out comes the Eaton catalogue and my mother points out a certain page to her with the models showing how she would like our coats to be made. “Fine,” says Mlle Elyse and she proceeds to take the measurements of my sister and I writing everything down on a scrap of paper, “You come back in two days for a fitting, and if everything is correct you will have your new coats for next Sunday,” said Mlle Elyse. We went the following Wednesday; our coats were all basted together, we tried them on. Mlle Elyse put a few marks here and there with her chalk and said, “Fine, you come and get your coats next Saturday afternoon”, and they were ready, she must have charged $1.25 per coat for sure because she was said to be “expensive”. They were very nice coats and had very nice little pockets.

How We Came Into the World

The word sex did not exist when we were young, at least I never heard it. One day I found out how I came into existence. On the 14th of August, 1923 my mother wanted to make cabbage soup, and she went to the garden to get a cabbage, they were extraordinarily large that year. She chose the biggest and she pulled it out, low and behold, under the biggest and largest leaf was the cutest baby girl that she had ever seen. She brought it into the house and washed the dirt off of it, and that beautiful bundle was me!

My sister Yvette was ordered from the Eaton catalogue! My sister Theresa came from Montreal because our aunt Aurore wanted to be a Godmother and she brought the baby with her from Montreal for my mother. One of our friends had freckles, and that was because her mother had found her in an old rusty pail! My brother? Well, he’s another story, for I was eight years old at that time. One day in June, my sister and I came home from school. Our sister Thérèse was only four years old and was not considered old enough to be fully aware of events about to take place. My mother said to us, “Your aunt Blanche wants to see you, and you are going to visit her”. “Why does aunt Blanche wish to see us? We have school tomorrow”. “You know aunt Blanche has no children and she gets very lonely, yesterday she asked your father and I if we could not send you two for a visit.”

“What about our school work?”

“I will send a note to the Sister; she will not mind because school is almost over for the year and all the exams are in; next week it will be finished.”

That made sense to us and we were very happy to visit our aunt. The tote bag was already packed with our nightgowns all we had to do was to go up and change our convent uniform into some other clothes and away we went. Our father did not take us. Instead, it was the hired man who drove the horse and buggy, we knew him well, he was an older man that was doing odd chores for us on the farm like taking the milk to the dairy, etc.

Aunt Blanche, my Godmother, lived about three miles away down the St-Lawrence River on top of the big hill, she was extremely happy to see us and welcomed us with big smiles and open arms and fussed over us a great deal.

The next day, soon after lunch, we were playing outside when we saw aunt Alice, another sister of our father. She was with her husband, uncle Antonio and our cousin Raoul, who was older than us, driving into the yard in their nicest biggest buggy driven by two horses. We rushed into the house to call aunt Blanche who came out as fast as she could. Everyone in the buggy had big smiles on their faces and seemed very happy. As soon as aunt Alice alighted from the carriage, she exclaimed the good news she had for us; she kissed us and said, “You have a baby brother!” We both cried out, “We have a baby brother! How come? Where did he come from?

“Well, last night when you came to aunt Blanche did you not see a big van with a tarpaulin flapping in the wind?” “Yes, yes, even the horse got scared, and Mr. Fortin had a hard time to hang on to it.” “Well, children, that van belonged to a band of Indians, and they went to your mother’s place, and they left a baby boy there, and you know your father’s cousin Nazaire?” (He had been married for 20 years and never had any children. His wife always wanted children.) “Well, that band of savages passed us on his rural route. He stopped them and caught one of them and told them he would kill him if they did not give his wife a baby, so now they have a baby boy too.” “That’s wonderful” we were speechless over all of that amazing news. Aunt Alice said, “We are on our way to your place to see the baby and have him baptized; your parents have asked us to be Godparents, do you want to come along?” Surprisingly, aunt, Blanche did not mind, and she was all smiles. We rushed upstairs, grabbed our nightgowns and were back in a flash. When we arrived home our mother was sick in bed, she had the grippe and couldn’t come to the christening. My grandmother was dressing a screaming baby into the flowered christening outfit that she had made when she was 20 years old for her first born. She had ten children, we were all baptized in that outfit, and my six siblings were also baptized in it. I still have most of it in an old trunk. My brother was baptized, Joseph Jean-Guy Antonio. I was greatly impressed with his behaviour. I loved him right away, and I still do. He still impresses me very much with his varied skills; there is no one else in all the world like him. My mother was 42 when he was born, and he was the pride and joy of her old age.

From my high-rise window overlooking the St. Lawrence Seaway, I see a big cargo ship heading for the Great Lakes. What changes our generation has seen! It was goélettes schooners that traversed the St. Lawrence in my childhood. There were sailing ships with no motors. The sails were a beautiful sight, like little white moths with their wings closed, swaying in the breeze, so small and fragile in the big river. A lot of pulpwood was shipped in those as well as all sort of supplies; it was the great highway. If the wind was at their back going down toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence, they must have made wonderful speed because they were not on the horizon very long. They were hardy men that sailed, and they told wonderful stories, sometimes frightening ones. I have known quite a few of them and held great respect for those fearless travellers.

Bread

Not everyone was baking bread, so one could buy from the baker who came to his regular customers two or three times a week. He had a covered wagon which was painted white and red on the outside, and all white inside also inside were many shelves and bins. The wagon was drawn by a horse that knew exactly where to stop from one client to the other. Bread wasn’t wrapped in those days. The baker himself wore a long white coat lab technicians wear; he had a leather pouch strapped to his waist to make change. He carried the bread to the house by the armful, often had so much in his arms it looked like corded wood. What we called one bread was two loaves, joined together the way hot dogs buns are today. You could buy one half which was the size of one bread today or a full loaf which was two halves, or one and a half loaves, etc. People could pay with light aluminum tokens bought from him. He also sold wonderful raisin buns; you could get three dozen for just 35 cents!

It was a treat when mother bought some. The baker went to all the rural routes at different days, stopped at his regular clients and at the different general stores that always kept some of this bread.

Our pantry was a well-stocked one. It was a room on the northeast side of the house with shelves from bottom to ceiling on one side. It had a trap door in the floor that gave access to the cellar below. On one side there was a table, one side had a large window. The spaces on the other side were lined with barrels. The box for the bread was a big square one that had originally contained tea. There was a barrel for the flour and one for the sugar. One always bought these items in 100-pound bags. There was always a long side of smoked bacon hanging there and crocks and jars containing pickles, salted herbs, plum jams, beets and more. The salted pork barrel, well weighed-down with a rock on a plate, was kept on the dirt floor in the cellar where it stayed cool in the summer heat. Molasses was kept in five gallons in earthenware jug, and the large roasting and baking pans were all hung up on hooks on the walls, there were also food scales hanging there; that was an important item when the time came for jams and jellies to be made. A big wooden pastry board was kept there as well as the pans to bake bread frying pans hung on hooks; leftovers were kept there also, it was a place where one could have some nice snacks. The shelves contained butter, a milk pitcher, cream, maple syrup, cakes under covers, and cold roast pork; it was the first place to hit after school, I tell you, Dagwood would have loved it!

Butchering Day

About 15 days before Christmas, we would come home from school for lunch, and there was a horrible smell was in the house! It was butchering day; seven or eight pigs were slaughtered along with one or two heifers. This was done in the pig house for the pigs and in the shed behind the barn for the heifers.

My father did not do it himself; there was a self-appointed expert for that sort of job. He was an obese old bachelor whom we were terribly afraid of. He had been kicked by a horse when a child and as a result, one of his eyes was much lower than the other, his face appeared slanted somewhat, his beard was always one week old, his hair was unkempt, his protruding stomach and the smell of him was enough to advertise his trade.

My mother had a half-dozen tablecloths made of bleached sugar bags sewn together especially made for this occasion. As soon as a pig was ripped open, the entrails were dumped into these white tablecloths and tied by the four corners; the brought into the house. My mother and my grandmother, or whoever was there to help that day had the job of removing all the globs of fat from all the innards of the pigs. These globs of fat were kept in a large basin of cold water and later on, when rendered, became a large pail of shortening.

Butchering Day, all the men helping with this task were coming in for lunch and were served, among other things, a blood fricassee made with the fresh blood of the pigs. They really seemed to enjoy it, but I could never eat it then. Today, I love blood pudding, blood sausages, heart, liver and gizzards. My husband called me “The cannibal” when I have a feast of those foods.

As I grew older, my mother greeted me when I arrived from school at 4.00 p.m. by saying, “Hurry up Lucille, go and change quickly, then come and help me.” The horrible smell of innards filled the kitchen. Mother was behind schedule. Lunch for the hungry mob delayed her. She was tired, and two or three filled white pouches were waiting for streamlining. Reluctantly I joined in and became educated about the inside of a pig which is very similar to that of a human being. As we proceeded, I was learned about the pancreas. The pancreas would indicate what sort of winter we were to have. If it was long, we were to have a long and mild winter. If it was lumpy, there would be bad stormy weather ahead. We kept a few threaded needles handy because every once in a while, our sharp little knives would cut one of the intestines, that accident would create a horrendous odour. It was sewn up in a hurry. It was a good thing mother had a great sense of humour. Time went fast doing this work. Soon we were at the end of the ordeal. We were finished!

Later, when I was 14 years old perhaps, I went to hold the pan under the throat of the pig while it was bled. They were hung by the hind legs and their front legs tied for that purpose no doubt. One had to hurry up to the house with the liquid, stirring it constantly until it cooled down. We kept stirring it in the pantry until it was very cool. I dreaded the piercing squealing of the pigs. As I write this, I am 65 years old, and I have yet to faint; it must have been the training I received in those days when one learns early the laws of survival.

A few bladders of the pigs four or five were saved up to make grandfather tobacco pouches. They were blown up with a straw until they were good size balloons. They were tied up with a string and hung up near the stove to dry; it was a process that took a few weeks. Once dried, the tops were cut off; they were rubbed together between the hands to make them pliable, it became the texture of very fine kid leather. Mother hemmed the top with red bias tape because grandpa was a liberal, blue would not have done at all. Men put their cut-up tobacco in it, twisted the top and it was a good tobacco pouch. Most farmers grew some tobacco plants, and they exchanged pouches when they met their friends to see who had the best harvest.

Young chicks huddling under the mother hen and peaking through the feathers are very lovable, but they grow up very fast. We continually fed them, then, on a nice summer Sunday, they tasted very good on the menu. Once I had a pet chicken, I started to pick it up when it was very young and fed it out of my hand, it soon recognized me. I would feed it choice morsels of leftover vegetables taken to the hen house. When that stupid bird saw me, coming it almost flew over every other chicken to get to me first. It flew right onto my shoulder. Squawking. It grew up faster than all the others, and sooner than the others, was he on our Sunday plate.

Our father was a good provider. 30-35 chickens adorned the shelves of the outside pantry in the winter; they also were killed before the holiday season. We spent a whole evening drawing them after the feathers were plucked and then passing them over the fire flames to burn off the hair that remained on their skins. A whole pig and a heifer were kept for us. The rest of the animals were sold to the local butcher, which provided cash. Once the meat was frozen at that time of the year, it was never a problem. We had rigorous winters, and it did not thaw until spring. Father took the pig and beef to his friend who had a furniture shop; he had a saw and father came back with all the meat cut according to the code of the butchers into roasts, slices of steak, stew meats etc. His friend was paid in meat. We had a very well-stocked outside pantry; we were only four children.

In the summer, we would coax my father to make us a gallon of ice cream. If he agreed, my mother would prepare the necessary ingredients early in the morning, using eggs, cream, flavouring etc. went into the metal container. In turn, the metal container fit into a gadget in a wooden bucket surrounded by ice. The ice had to be ordered the day before, and it came in a big square block which was kept on jute sacks in the cellar. It was quite a job, for the ice had to be broken into little chunks that could fit between the metal container and the wooden bucket. Father would turn the handle which activated the beater inside the container by a little wheel on the top. As the ice melted, he added some more. He turned the handle on the side of the bucket until he could not turn it anymore, that meant that the ice cream was ready, and oh, what ice cream! Once in summer, we coaxed him to take us on a picnic, usually on a nice Sunday afternoon on the same day the ice cream was made. This had to be organized the day before because the ice to be ordered, there was a crock of beans to be baked, full boxes of sandwiches had to be made and lemonade to be prepared.

When everything was ready, father hitched the horse to the wagon and in went the bucket of ice cream. It was well-packed in ice and covered with sacks. The pot of pork and beans was covered in blankets, along with a large box containing the rest of the lunch. Our mother even brought glass dessert dishes and all the paraphernalia for the ice cream. A couple of friends had been invited along with the children and the dog. When everyone was ready and the wagon well-loaded, we all went to the maple sugar bush. It was very pretty in the bush in the summer; the Sun would shine through the green leaves, and it was calm. Papa would get a table out of the cabin. Mother would set the table, with a tablecloth, and we had our meal under the trees. The beans were still very hot; the home bread was delicious, sandwiches excellent, ice cream divine!

These once-in-a-summer extravagant picnics stand out in my memory, and when I think of all the trouble my parents went through to give us these beautiful days to remember it, erases all the hardship we had to go through growing up. The sky was blue, the flowers were bright, the butterflies very pretty, and we sang all the way back home. I am sure that my father slept the slumber of The Just that night because he had made his children happy.

To finish these reminiscences, my dear girl, I will write the words of the ballad you liked to hear me sing. It must have been created around the time of World War I, or prior to that. Can you sing it? It would be fun to mime.

Le Petit Grégoire

La maman du petit homme

Lui dit un matin

A seize ans t’es haut tout comme

Notre huche A pain

A la ville tu peux fairs

Un bon apprenti

Mais pour cultiver la terre

T’es bien trop petit mon ami

T’es bien trop petit dame oui

La guerre éclate en campagne

Au printemps suivant

Et Grégoire entre en campagne

Avec Jean Ghouan

Les balles passaient nombreuses

Au dessus de lui

En sifflottant dédaigneuses

Il est trop petit ce joli

Il est trop petit, dame oui

Cependant, une le frappe

Entre les deux yeux

Par le trou l’ame s’échappe

Grégoire est aux cieux

La St-Pierre qu’il derange

Lui dit: Hors d’ici

Il nous faut un grand archangel

T’es bien trop petit mon ami

T’es bien trop petit, dame oui

Mais en apprenant la chose

Jésus se facha

Entrouvrit son manteau rose

Pour qu’il s’y cacha

Fit entrer ainsi Grégoire

Dans son paradis

En disant: mon ciel de gloire

En vérité, je vous le dis

C’est pour les petite

C’est pour les oetits dame oui.

Little Gregory

The mother of the little man

Said to him, one morning

At sixteen you’re as high as

Our bread hutch

In the city, you could do

A good apprentice

But to cultivate the ground

You’re much too small my friend

You’re much too small yes ma’am

War breaks out in the country

The following spring

And Gregory goes into campaign

With Jean Chouan

Bullets were passing numerously

Above him

Whistling disdainfully

He is too small this pretty one

He is too small yes ma’am

However, one hits him

Between the two eyes

By the hole the soul escapes

Gregory is in heaven

There, St-Peter whom he bothers

Tells him: Get out of here

We need a great archangel

You’re much too small my friend

You’re much too small yes ma’am

But learning of the event

Jesus got upset

Threw open his pink cloak

For him to hide in

Let Gregory in this way

Into his paradise

Saying: my heaven of glory

In truth, I am telling you

It’s for the little ones

It’s for the little ones, yes ma’am.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

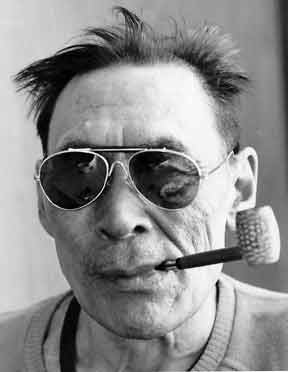

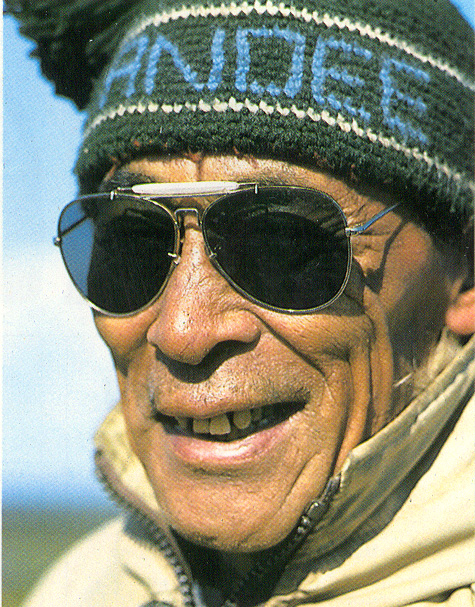

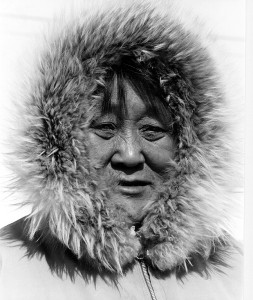

Eric Anoee, A Friend Remembered by Bill Belsey

The Inuit Writer and cultural activist was a man capable of great wisdom and generosity to friends – whatever their heritage.

His face was deeply tanned, wrinkled and familiar, like a fine old leather jacket. The eyes, hidden by ever-present sunglasses, were tired, yet not without a sense of possibility. There was a gentle, measured cadence and tone to his voice that implied wisdom without ego, thoughtfulness based on hard-earned experience, and knowledge without prejudice. This was Eric Anoee, a man I had known for all too short a time. Anoee was born in the Kazan River region in about 1924. His mind was always full of wonder, and he understood the power of knowledge early in life. He learned the old ways by watching his father and relatives in the land, and he studied the ways and language of the Qabloonat through the missionaries and their books. This love of learning stayed with him throughout his life. Others regarded him highly because of his increasingly rare understanding of traditional Inuit practices and the richness of Inuktitut.

Anoee became a catechist for the Anglican Church in 1962 and was asked to be an official interpreter for two bishops. In 1965, he started to publish an Anglican magazine. He became a Justice of the Peace and lived in Pangnirtung for several years, where his election to the local council recognized his stature. Soon after the Inuit Cultural Institute in Arviat was formed in 1974, Anoee became a researcher for the Inuit Tradition Project and, in 1975, was appointed its director. He oversaw the recording, transcribing and editing of his people’s cultural heritage and traditions.

The Eric Anoee Readers, written and illustrated by Anoee himself, are used by teachers and classroom assistants to teach Inuktitut throughout the Eastern Arctic. His writing has appeared in Up Here (October / November 1989) among other magazines and in Northern Voices, an anthology edited by Penny Petrone and published by the University of Toronto Press.

When I first met Eric Anoee in 1982, I was embarking on my first full-time teaching job, joining a staff that would be trying to teach over 200 students in a building without interior walls. Eric Anoee would teach Inuktitut to my grade four class. His tranquil, pipe-filled smile immediately warmed me as we shook hands. During that first year of teaching, Anoee was away for several days; I feared he was sick, but didn’t ask anyone. After returning, he politely mentioned “meetings in Ottawa”. It wasn’t until over a month later that I learned he had been south to receive the Order of Canada from the Governor-General for his contributions to education and Inuit culture.

In subsequent years, Anoee would lead Prime Minister Trudeau and the other first ministers into the National Conference Centre in Ottawa to give the opening prayer in Inuktitut for the first conference on Aboriginal issues. During the 1986 Inuit Circumpolar Conference in Kotzebue, Alaska, Eric Anoee was one of the most respected elders invited to address the meetings. On October 16th, 1991, then Northwest Territories’ Education Minister Steven Kakfwi posthumously recognized Anoee with an award for his contributions to literacy in the Northwest Territories. While honours and accolades often came his way, Anoee took his greatest pleasures from his family, his time on the land, his art and his omnipresent pipe. Due to a progressive illness, it became more difficult for Anoee to spend time on the land in his later years. However, it has been said that in his prime, Anoee could build a finished iglu in 45 minutes and completely butcher a bull caribou in less time. Anoee had the respect of his fellow hunters. In subsequent years, Anoee would lead Prime Minister Trudeau and the other First Ministers into the National Conference Centre in Ottawa to give the opening prayer in Inuktitut for the first conference on Aboriginal issues.

Whenever I visited Anoee, I felt overwhelmed by his family’s hospitality. On my first visit, I knocked at the door (a formal habit that I later unlearned), brushed the snow off my sealskin kamiks and edged inside. The porch contained an unfinished wooden shelf unit that looked like a shop project from school, loaded down with the kinds of odds and ends that are essential to Northern settlement life: a litre of 10W 30 oil, two recycled NGK9BR spark plugs, a drive belt for a Yamaha 340 snowmobile, snow knife, a well-used Coleman stove, a can of Naphtha, a greasy toolbox, and a handful of .22 calibre bullets.

The living room was spartan, yet welcoming, with a large grey chesterfield that showed signs of child erosion. Across from the couch was a crucifix and a painting of the Virgin Mary beside it. A broad, lime-green wooden table was surrounded by three chairs that could have come from a 1950s diner. In the corner of the living room was the ubiquitous 30-inch television, tuned to Hockey Night in Canada. Anoee’s wife, Martina, brought us a huge pot of tea made from Wolf Creek ice, guaranteed to yield a better-tasting brew than you could make with trucked-in, chlorinated water. A steaming plate of bannock fresh from the frying pan followed, and a pot of caribou stew (uujuq).

During other visits, I would be ushered to his bedroom, where I often found Anoee reclining upon a single, well-worn mattress, no box-spring, thank you, upon the floor. His CB radio would be squawking out messages from settlements and camps across the North. The aroma that wafted from his old corncob pipe permeated his room. Anoee carefully blended Erinmore flake pipe tobacco with a crop of low bush cranberry leaves, harvested at a precise time each fall. They were roasted and cut so that even in the darkest January, the effect upon the senses was like walking on the autumn tundra.

In this setting, I passed many a warm, memorable evening. Anoee might show me a painting or carving he was working on or ask me probing questions about how to best use his new camera. Another evening, he might tell me a story or teach me a string game. Before knowing him, I had always felt awkward with silence during a conversation; Anoee reminded me that silence gives you time to listen and think. He often sang and laughed readily. This is how I remember Eric Anoee before he died on September 24, 1989, in Arviat. On March 19th, 1991, five days after the birthday of Eric Anoee, my wife Helene and I were blessed with a son. We asked our friend, Elisapee Karetak if she would take a message to Martina Anoee, who did not have a phone. We wanted to ask her if we could name our son after her late husband.

Elisapee phoned to tell us Martina’s enthusiastic answer was “Yes!” The Reverend Armand Tagoona baptized our son in Rankin Inlet. The relationship between Tagoona and Anoee had been a long and close one. As he poured the holy water gently over the baby’s head, Armand smiled and whispered, “Welcome back, my friend.”

To this day, I cannot begin to tell you how good it feels to look at my son and say, “I love you, Anoee!”